Want to hear more from the actors and creators of your favorite shows and films? Subscribe to The Cinema Spot on YouTube for all of our upcoming interviews!

Paul Thomas Anderson’s Licorice Pizza was technically released in November, so this review may be a bit late to the party, but hey, my closest theater is in Fairfield, California. It’s known less for its appreciation of movies and more for being the headquarters of THE Jelly Belly Factory, so cut me some slack.

Sadly this is not a movie about Jelly Bean pizzas, it’s about licorice pizzas. Although, licorice is inferior to Jelly Beans (this post is not sponsored by Jelly Belly), let’s first get on to the movie… trailer.

Trailer Consideration

I think it’s important to start with the trailer. After reading a bunch of other reviews on the movie, it seems to be the only thing most people watched, or we watched different movies. Licorice Pizza is not about an arguably pedophilic relationship between a 25-year-old woman, Alana Kane (Alana Haim), and a 15-year-old-boy, Gary Valentine (Cooper Hoffman).

Does the story center on the developing relationship between the two? Yes. But the relationship takes a backseat to the interesting exploration of masculinity and femininity in a world where we are responding to — and largely perpetuating — the values of a previous generation.

I grew up loving indie-type romantic comedy movies. I’ll admit it. Adventureland, Juno, other Michael Cera movies, etc. And the trailer for Licorice Pizza, to me, read like a movie in this vein, albeit much less early-2000s and much more cynical, very 2021.

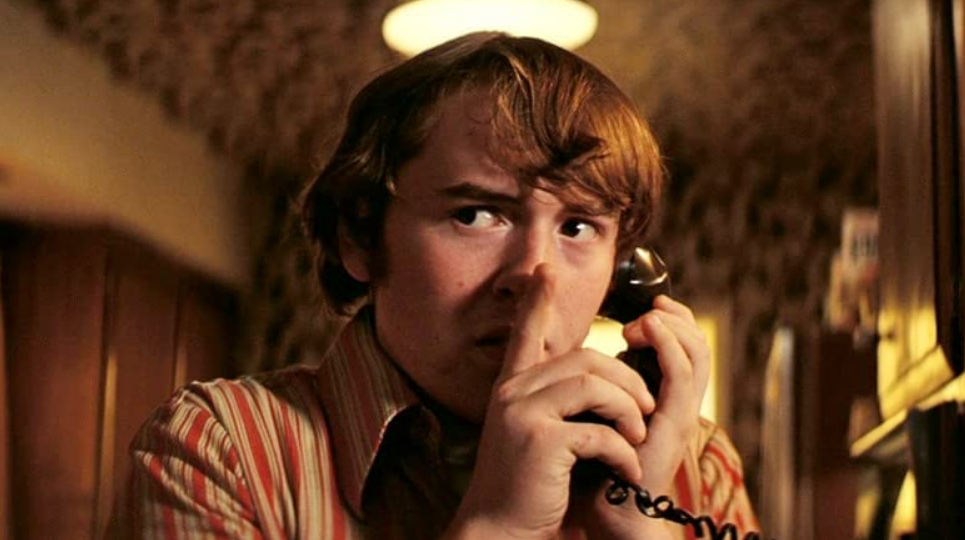

Hoffman’s Gary looks real. He looks like a teenage boy with some acne or blemishes on his face. He’s not all dolled up and it looks authentic. Hell, he plays it authentic and it shows. Haim’s Alana looks and acts like a real young woman. She’s fed up with his sh*%, and her unglamourous position in the world, and it shows.

While it seems like it will be a pleasant rom-com, maybe with some added -dram, things are messier and explore some complex social dynamics that the movie, this review, and anyone reading it can only start to tackle.

The title sounds gross, teenagers are gross, we are all kind of gross, and love is no exception. Just because something is gross doesn’t mean that the emotions involved, even in teenage love, aren’t true and intense and heightened and real. However, that is an interpretation of the trailer. Licorice Pizza as a full-length movie does so. Much. More.

Let’s finally go to the movie! (Warning: Spoilers ahead)

Movie Time

Licorice Pizza explores the masculine experience of control and desire, power exertion and performance, and the interconnection of these things; the film (I believe) focuses on a feminine experience beholden to the male gaze and a sort of self-actualization to become the male’s object of desire in response to this forced positioning. Yes, it’s through the lens of an odd coupling between a 15-year-old boy and a 24-year-old woman. However, the focus on this as a theme is rampant and on display in practically every scene.

I don’t think this movie is saying this is the only experience of male-female relationship dynamics. This is a question raised by Catherine Shoard at The Guardian. While this isn’t a direct condemnation of touting this experience as universal, it speaks to the specific context that Anderson has decided to work within. That choice can be questioned as an aside to the movie.

My goal here is to explore more of the story as its presented and the responses that follow (contextualizing to suit my argument, I will admit it).

The story goes through phases of the relationship. Primarily, these seem to be ways that Gary views Alana, and how she responds. I think the movie centers on Alana. It is framed from the lens of her male “suitors” but she is the protagonist. The film is written and directed by a man — Paul Thomas Anderson — so right off the bat, Alana is created and displayed as a character through a male lens. Although, I think Anderson is acutely aware of this, deciding to focus on it and dive headfirst into it in the very first scene through to the final one.

Here are the phases of Gary’s view of Alana that I find interesting:

Phases of “Relationship” in Licorice Pizza

- Future wife

- Someone else’s “future wife”

- Object of physical desire

- Cast aside desire

- Someone else’s object

- Platonic, though physically desired partner

- Someone else’s “respectful” partner

- Respectful romantic partner (?)

In the first scene, Gary and Alana meet at Gary’s school on picture day. Here, Alana is one of the photographer’s assistants (which if I now remember correctly, are all young women). They converse, he charms her and she somewhat just responds to it, not having to charm the teenage boy beyond simply being a woman. As the scene ends, Alana walks away from him and goes back to her post, and the photographer, out of seemingly nowhere, slaps her butt. She smirks, annoyed, but she seems to be used to it.

After this brief, mere minutes-long encounter, Gary goes home having asked Alana on a date. And the roller coaster begins.

Future Wife

Before the date even starts, Gary describes Alana as the woman he’s going to marry someday to his even kiddie-r brother. It reads as a sort of innocent viewing and want, lacking any real desire for possession. That will become a learned behavior.

Initially, Gary does not have any other males to compete with (from his perspective). Not only in terms of Alana, but also within his whole social life. His father is not present, his brother is 9 years old, and we later see he is the leader of his group of friends.

For all intents and purposes, Gary — down to how he acts and presents himself — is the “man of the house.” He occupies a position that starts off unproblematic and how he acts towards Alana doesn’t seem terrible. (He presents himself as manipulative and too controlled during their first date, but this could be tainted now by my whole viewing of Licorice Pizza.) Well, he’s not totally terrible yet…This changes when another male “competitor” enters the story.

Someone else’s ‘future wife’

While Gary and Alana don’t initially become a romantic couple, they grow closer as friends. They travel together, her as his chaperon, to some sort of promo spot for a movie or television show Gary was in, playing what appears to be an even younger child. On the plane ride there, another of the kid actors, Lance (Skyler Gisondo) introduces himself to Alana. He makes a benign comment about the airplane food, asking how her meal was. She responds, liking the attention. Gary is evidently ruffled by this “flirting” becomes short and gruff when he butts into their conversation.

They get to the promo event, and Gary tries impressing Alana with a beaver joke that is not taken all that well by the lead of Gary’s troupe. Lance impresses her more though, and they eventually begin dating. The majority of the scenes that immediately follow are from Gary’s perspective as he pines over his “lost love”, and the movie sets up Alana as this “thing of desire” for Gary.

Side Note

However, there is a scene where Alana brings Lance home for a Shabbat dinner with her family. Jewish identity is explored in the scene — and more in the movie — but it was not something I was very aware of while watching. I think it could be analyzed more than I possibly could do justice, but pondering on this brought me to a Forward article by PJ Grisar, where he discusses these interesting nuances.

The scene finds Lance rejecting his Jewish heritage and “respectfully refusing” Alana’s father when asked to say the hamotzi, a type of prayer/blessing. In the immediate scene after, the couple leave Alana’s house where she asks Lance if he’s circumcized. When he finally coughs out that he is, she yells, “Then you’re a f—ng Jew!”

For the sense of my review/argument, consider Grisar’s words: Alana (and the movie) “has reduced Jewishness to a physical trait, and has had hers reduced in turn.” Alana as a character is not much interrogated in these moments except in her response/reaction to her male counterparts (Lance and her father). In the dialogue that she has (that I can recall) she does what Grisar notes as reducing something to a physical trait.

This reduction to physicality seems in line with her positioning herself as an object in relation to the men who show her interest. This is largely why Licorice Pizza reads as extremely sad and disgusting to watch for me, not that innocent indie rom-com-dram that I was expecting!

So Gary and Alana do their own things for a little while, but once her relationship with Lance fizzles out, the two start hanging out more again. And now, Gary has been influenced by his competition and little boy hormones, allowing him to reposition Alana as an…

Object of physical desire

Gary becomes (or at least starts to show) his lustful desires, no longer simply wanting Alana as just an intense friend. The two hang out more, going to casting agents for Alana or working on shared business, with a heightened awareness of specifically Alana’s boobs.

This leads to a scene where Alana shows Gary her boobs after he whines about her saying she’d be willing to show them to countless people in a movie if she got the part. This period continues and elevates Gary’s perceived or desired ownership/control of Alana. While on the way to see the casting agent, he tells her to say yes to everything, it will help with getting a part. Lie about whatever, she can learn it later is what he claims (this mentality reflects Gary’s own, showing he is manipulative snake oil salesman, something that should be explored even more in its own right).

The fact that he goes into the meeting with her is further odd and invokes the feeling of a father or guardian accompanying their child to a meeting. Regardless, after the meeting and Alana’s following of his advice and saying “yes” to all questions, including one about being willing to go topless, Gary is livid. He complains that she won’t even show him her boobs and is a hypocrite and… Then he’s rewarded?

Alana storms off but then returns and succumbs to Gary’s complaints and possessive nature. It makes me feel gross for the whole situation and Alana’s self-esteem in particular. But don’t worry, it gets worse. Now that she has given in to Gary’s view of her as an object of physical desire, she gets to become his…

Cast aside desire

Once Alana succumbs and gives in to Gary’s desires, she can no longer function as what Lacan declares objet petit a. She becomes attainable. This removes power from her over Gary, which she both experiences and performs in scenes that follow. Gary moves on to a younger girl from his school, and at a big event for their waterbed company (sorry, forgot to mention they start a waterbed company because Gary’s charm can’t distract me from the atrocious positioning of Alana in relation to Gary and the men that will follow) Alana is relegated to being advertisement or entertainment for “potential clients.”

She is one (if not the) only person wearing nothing but a swimsuit that Gary ogles before the start of the party. She’ll fight, and fail, to gain the attention of Gary once he moves on to the younger girl as well as the attention of anyone entering the event. She eventually leaves, but the damage is done.

I started to think that maybe Alana would realize how sh*%%y Gary is, and really just men in general towards her! But no, that would be too happy and not in line with a large part of modern cultural values of women and this movie is not trying to be happy… I’m starting to think of Luis Buñuel’s That Obscure Object of Desire, in which two women play the same role and the lead male is none the wiser, with similar fates to Alana’s fulfilling the male’s necessary objet petit a. Thus, viewers are left to watch Alana become…

Someone else’s object

From Gary’s perspective, Alana moves on to become someone else’s object. I believe that he moves on to incorporate Alana as both a physical desire and a relationship desire, though how to define a relationship is another task in its own right. Alana goes out for a drink with an older man, William Holden (Sean Penn). He is a hyper-masculine actor she would star alongside in an upcoming production seeing Alana as “Rainbow.”

They go to the place Gary and Alana first go on a date to — featured prominently throughout the film as Gary’s spot, and Alana’s by extension. Only by extension though. It is named Tail o’ the Cock, needing no further introduction. It’s fitting that this key location in the film is so phallic because in this part particularly, everyone starts whipping around their d—you get the idea.

Gary finds himself at Tail o’ the Cock that same night with several young girls. He sees Alana and demands to sit in view of her. William Holden gets drunk and reminisces about his old glories, heightened by a friend that soon shows up. He talks to Alana about (I think) sad stuff she doesn’t listen to or care about. And she talks to him about if she’s pretty, also drunk.

This scene fascinates me because it highlights the disconnect between male and female, at least in the context of the movie and possibly more globally in heterogeneous monogamous relationships. Gary is jealous of Alana and only desires her now because she is “with” this other guy though she is not even interested in the other guy but is just seeking some sort of validation from this other guy who is not even interested in Alana for any other reason than to talk at and fulfill some glory day memory he is clinging to. They all treat the other as objects here and none actually communicate with one another, but some sense of desire becomes generated through lack of something.

In the climax of Licorice Pizza, Holden performs a stunt jump on a motorcycle, Alana falls off the back, and Gary runs out to make sure she is ok. They embrace and there is some sort of acknowledgment of each of their desire for the other. They then move on, from Gary’s implied perspective to being…

Platonic though still (physically) desired partners

This time they are partners in a more equal sense, but this phase does not last long, really only a scene or two, which goes to show how fragile and fleeting their dynamic is. They begin doing separate things again, both pursuing different interests with mild overlap, and Alana becomes…

Someone else’s partner

Alana has some… sort of relationship starting with LA city councilman, Joel Wachs (Benny Safdie). She starts working for him, believes he’s a great man who is doing things for others, unlike Gary who is always just pursuing get rich quick schemes (see waterbed business), and Gary gets jealous.

They drift apart as he starts his new business, capitalizing on a law reversal that would shortly allow pinball again in LA that he overheard from Wachs himself. And this is where I truly lose my sense of people’s motivations beyond simply doing what they’ve done before.

Alana is invited to a drink with Wachs, but once there finds out he is gay, and is just using her as a cover for him because he is in the closet and being followed. Alana goes home acting like Wach’s boyfriend’s girlfriend—still following?—where through the boyfriend’s helps realizes or acknowledges that all men are “shits.”

You know, boys will be boys???

This allows her and her (and society’s) warped sense of reality to forgive and forget everything bad about Gary, and considering I don’t know what’s actually good about Gary, it’s A LOT. She runs to the Pinball Palace as he’s started searching for her, and eventually they find one another on the dark romantic streets of LA in the 70s. Barf. Now they become some sort of…

Respectful romantic partners (?)

The movie’s ending is fitting for a 2010s rom-dram-com, but not with a satisfying ending for the 2021 movie it actually is. The ending makes sense, but I don’t feel good about it. Maybe it is a fitting end for the time, there is no answer, no solution, no way to move past the present. It’s just a reflection of the culture we live in. It is not an ending that should make a viewer happy. They end up together, and Alana says she loves Gary. And I couldn’t be more uncomfortable.

Final Thoughts on Licorice Pizza

Throughout Licorice Pizza, Alana reconciles her life with the interplay of Gary’s desire and view of her and other men. Men treat her as an object from the very first scene. Her boss, the photographer slaps her ass as the first scene ends. Bradley Cooper’s character ogles over her which I didn’t even get to. Sean Penn’s character does too, and the fact that she ends up “loving” Gary hurts to watch.

I think this movie speaks largely to the internalized misogyny experienced by young (and older to old) women. It isn’t about the weird, quasi-pedophilic relationship between a 24-year-old woman and a 15-year-old boy. That is simply the backdrop.

There is so much at play here with Alana through the eyes of Gary that it’s hard to cover in one article.

If you haven’t seen the movie, there is plenty that I didn’t mention for you to discover (just look at how any other males in the movie views Alana more closely). There are so many different ways for you to be disgusted by the male gaze and its effect in Licorice Pizza. I urge you to find them and give me more reason to love-hate this movie.

And if you have seen the movie, please tell me if or why you liked it or hated it, or am I just having this insane response in a vacuum?

One Comment on “‘Licorice Pizza’ (Or How Everyone Seems To Love Internalized Misogyny) Spoiler Review”